In the Foreword to Monica White’s book Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement, LaDonna Redmond writes, “The contributions of people of color and indigenous nations are missing in our understanding of food history. Our legacy has been erased.”

For Black History Month, GrowNYC will highlight partner organizations and people working to present a counternarrative, inclusive of the history and invaluable contributions of Black farmers, agriculturalists, chefs, thinkers, and food advocates.

COMMUNITY

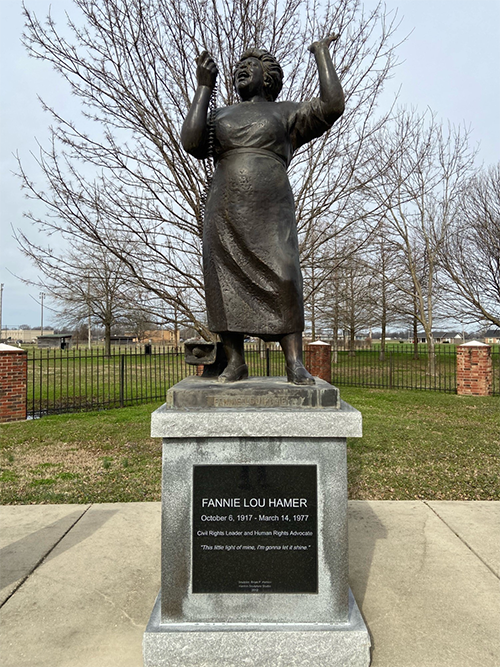

Fannie Lou Hamer, the subject of our final Black History Month post, is so indomitable and inspiring that you might find her featured again next month in GrowNYC’s Women’s History Month coverage.

In 1963, Hamer was severely beaten, almost to death, while in jail for assisting Black people in Mississippi to register to vote. Hamer was not deterred, and she worked on Civil Rights issues throughout her life. She was one of the main organizers of Freedom Summer, a voter registration drive in 1964 to increase the number of registered black voters in Mississippi, and she co-founded both the National Women’s Political Caucus and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

Another aspect of Hamer’s civil liberties work focused on agriculture and the importance of food sovereignty.

In the late 60’s, Fannie Lou Hamer bought 40 acres of prime Delta land and founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative in Sunflower County, Mississippi, allowing poor residents of Mississippi an opportunity to have a say, and stake, in the production of the food they eat. Hamer said that food “allows the sick one a chance for healing, the silent ones a chance to speak, the unlearned ones a chance to learn, and the dying ones a chance to live.”

Her work and ideas have been profoundly inspirational to many, including GrowNYC’s Green Space team who work on Community Gardens throughout the City.

One of these gardens is the Nehemiah Ten Community Garden in East New York. We recently spoke with Teresa Girard-Isaac, one of the 10 women (from 10 different countries) that originally comprised the garden, about the Nehemiah 10.

GrowNYC: Why was the garden started by women?

Teresa: It wasn't on purpose, just the kind of way it happened. Block by block, house by house, it was the women that came around. The men came out after. I’d be happy to have more men. Bring them on!

Everybody involved in the garden is from a different country. I think it has to do with then everyone bought their houses. I'm from St. Lucia, and Ms. Ana is from Puerto Rico. There are women from Guyana, Trinidad, Barbados, Grenada. Ms. Hassan from Egypt. Every house in this neighborhood is a different nationality.

GrowNYC: Where did your interest in gardening come from?

Teresa: I was not interested in agriculture. My husband's family grew up farming. My mother's family had land in St Lucia. I picked mangoes as we walked along the road…mischievous children. My mother's people were into working the ground. Her parents had lots of land and all kinds of fruit, but I didn't grow up gardening. It's kind of strange that I ended up being so involved in a garden.

I grew up in St. Lucia and got married in 1981. Then I was up here in 1982. We moved to Crown Heights, on Sterling St., but we always talked about wanting a house.

My daughter went to Hotchkiss and wrote the most beautiful essay about East New York. I was stunned at the ay she saw the neighborhood. She saw beautiful things and beautiful gardens all over the place—and this is when it was really bad, but she didn’t see it that way at all.

GrowNYC: What do you especially enjoy about being involved in the garden?

Teresa: I used to be anti-social and shy. But being in the garden has helped me so much, and now I talk to people all day.

I like the idea of growing fresh food, especially cucumbers. I don’t have to think about pesticides. I can eat the skin and not worry about it. When I first moved here, I planted flowers in front, and people would steal them. All of my yellow flowers would be gone in one day. But now I can grow my own peppers and it reminds me of the countryside of St. Lucia.

So many of our other members grew up farming, and it reminds them of their childhoods. You can say that it grew on me. It took me a while, but I enjoy it so much now.

In East New York, people's yards are full of fruits. One woman has a banana tree growing in her backyard.

I learn about different foods through the garden, but I also learned about different ways of raising children. We all have differences, I can't lie about it. The garden is a great place to learn.

FOOD

Edna Lewis is a clear standout among our farm-to-table heroes here at GrowNYC. She was a fervent champion of GrowNYC’s Union Square Greenmarket and of using local ingredients. In fact, in her cookbook 'In Pursuit of Flavor,' published over 30 years ago, Lewis references some of our farmers that still come to sell at Union Square today. It would be impossible to discuss the history and inestimable contributions of black chefs and thinkers without acknowledging Edna. She is perhaps the most famous, but other unsung black culinary pioneers, like Flora Mae Hunter and James Hemings, are beginning to receive the recognition they deserve.

The granddaughter of a former slave, Edna Lewis published her first cookbook nearly five decades ago, and ever since she’s been teaching people all over the world to love the flavors of the South.

She once wrote, “Greens are a dish that most Southerners would walk a mile for.”

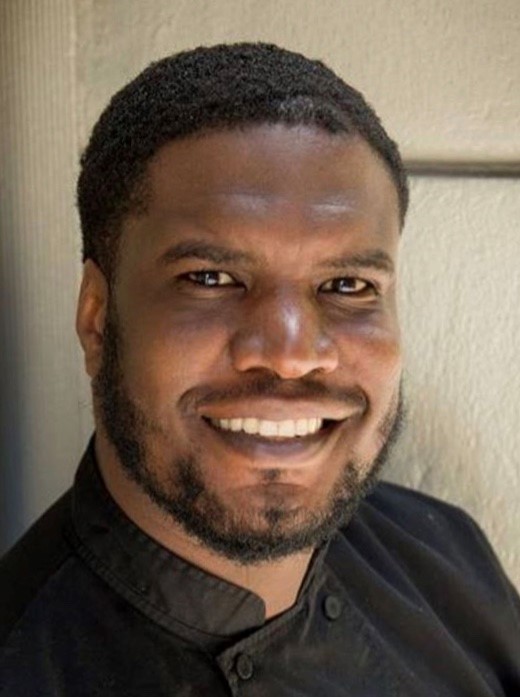

This week, we spoke with Kia Damon, who, like Edna Lewis, is an avid cook who moved to New York City from the South. Although Kia is only in her mid 20s, she’s electrified the NYC culinary world. And Edna Lewis is one of her heroes, too.

GrowNYC: What are you doing in the food universe these days?

KIA: Right now, I am the Culinary Director at Cherry Bombe Magazine. I used to be an executive chef, but I’ve shifted gears a little bit and am now dabbling in food media. Within my job there is a whole lot that I do and a whole lot that I have yet to do just because it’s a very new position It’s a still blossoming brand and media group. Right now I spend a lot of my time recipe testing for our next cookbook, trying to do great community work, and making the job interesting.

GrowNYC: When you were on a panel at MOFAD about Edna Lewis last year, you mentioned you have a tattoo of Freetown on your arm. Is that a nod to Edna?

KIA: Oh absolutely. I said to my friend in Florida who did my tattoos, “Can I get a quick little something?” He’s like, “What do you want?” “Just Freetown, Edna Lewis’ birthplace, on my arm. Hahahha.” He said, “You want to do Freetown, Virginia?” But I didn’t want that. Then everyone would think I was from Virginia. Just like everyone think’s I’m from Detroit because I have a ‘D’ on my arm for my last name. I feel like just the word ‘Freetown’ in itself invokes really good feelings in me, especially when things get difficult. It just feels good to look at it. It brings me back to where I was when I got it, so that I can remember why I do the work that I do.

GrowNYC: What is it about Edna Lewis that you admire?

Kia: For a lot of Black folks, American and otherwise, we go a while before we see other people in the food world (or other people’s respective industries) that we can reflect ourselves in. I grew up watching Food Network and Cooking Channel shows. I felt like those chefs were great, but none of what they did seemed attainable because, innately, I knew that that wasn’t my story, those aren’t my circumstances or privileges. Then I came across Edna and I was like, “ooh!” Here was this very tall, wise-looking, gentle-looking woman making phenomenal, delicious food, and food that seemed very relatable. And not relatable in the sense of food that people project onto African American communities, but just food that was really good. Food that I felt I could, and that I wanted to, make. And the way she highlights and cooks with the seasons…The first time I heard of ‘farm-to-table’ was from a Chef’s Table episode – I was like, “Oh wow. I want to do this.” And then I read about Edna and she was doing this from way, way back. Then I’m like, “wait a second, we were all doing this way, way back.”

GrowNYC: We are all about the seasonal--and regional--cooking here at GrowNYC. Do you incorporate this into your work?

Kia: Yeah. Well, more so in Florida. I spent time interning on a farm and working on a farm. I was growing microgreens and feeding the animals. In Florida, it was easier to work with the seasons. I worked at a farm and I worked a restaurant that used the produce from the farm. It was very community oriented. Since I’ve been in New York, I’m still trying to get a grasp of what the hell is in season and what the growing periods are and, really, what’s going on. Now that I’m out of the restaurant I will probably have more time to talk with farmers and speak with communities, and to have my own garden, and get back into it. Honestly, that’s where I feel the most together. If I’m not cooking, I want to have my hands in some soil-- being able to literally sow seeds, and put love and care into them. To see the thing grow and then nourish you, it’s the most basic and fulfilling cycle. It just hits you really deep. It’s something that really puts me in tune with myself and with past & present. A great feeling.

GrowNYC: I’ve noticed that you often talk about community in interviews. Why is that?

Kia: Being from the South and then coming to the North, where things are much more fast-paced, the way community looks and works is a little different. I feel like it’s a lot harder to find that sense of community. Even though everyone is hanging out, I feel like it’s harder to do work that feeds back into other people as it feeds back into me. I am trying to do work where I can meet people face-to-face. Being seen all the time, I feel like who I actually am has started to become invisible. It becomes difficult to talk to people because the only thing they can interact with is the person they’ve projected me to be from what they’ve seen on the Internet or these other spaces. I really can’t keep up in that way, and my only default is to just retract from it all. Then I end up isolated. So now I am like, how do I break away from that? I’m going to talk to people face-to-face, and I’m going to be side-by-side with people, whether it’s in the dirt or with the crops or at the restaurant or whatever. I know things don’t look the same as they did when I was home, and I know I can’t change that. So, how can I change the way I interact so that I can still find that sense of community. I am devoted to the people and to the community. Not in a weird superficial way, but with authenticity. And I’m still searching to find it.

GrowNYC: I wonder if Edna Lewis ever felt something similar, coming up from the South. If you could talk to Edna and ask her just one question, what would you ask?

Kia: Wow. If I could ask Edna Lewis anything…? No one has ever asked me this before. I would ask her what she envisioned when she decided to leave Virginia and go to NYC. Was she doing it for other people or was she doing it for herself? I would love to know what she saw for the future of food.

Learn more about Kia via her Instagram @kiacooks and @cherrybombe

LAND

To put the extensive contributions of Black farmers, agriculturists, and chefs in perspective, consider the Pigford v Glickman Lawsuit of 1997.

In 1920, there were nearly a million Black farmers in the United States. That number plunged over the years due to decades of racial discrimination and the unlawful denial of loans to black farmers by the USDA. In 1997, Black farmers in the South filed a federal class action lawsuit, seeking to end this legacy of bigotry – and they won. Pigford vs. Glickman was settled in 1999. It was a followed by another suit, Pigford II, which was settled in 2010. Although the settlements reached into the billions, they are just a tiny drop in the bucket. This 2019 article from the New Food Economy discusses the inadequacy. In addition to payout problems is the fact that the settlements resulting form the Pigford lawsuits deal only with relatively recent claims of discrimination resulting in refusal of loans and even foreclosure, “and none stretching back to the period of the civil-rights era, when the great bulk of black-owned farms disappeared.”

Today, Black farmers (1.3% of total number of farmers in the US) own just 0.52% of our farmland.

LaChaun Moore took GrowNYC’s Whole Farm Planning course in 2018 in preparation for a move to South Carolina to cultivate organic naturally colored cotton for her “farm to textile” venture. We recently asked LaChaun a few questions about her work and her influences. In her thoughtful response, LaChaun reflects on this notion of the land, dating back well before the Civil-Rights era.

GrowNYC: Is there a particular agriculturist, grower, chef, historian, etc. that influenced you?

LaChaun: There are quite a few, however, what has inspired me throughout this journey is my ancestors-- the generations within my family as well as the many black bodies that were captured during the transatlantic slave trade. My grandfather was my first introduction to agriculture. He and his five brothers were sharecroppers. I grew up hearing stories about how they had to steal away in the night to escape the Jim Crow South by pushing their car in the dark dead of night with the engine off until they made it to the main road where they took off to Philadelphia. They did this to avoid waking their sharecrop overseers who, in that era, were next of kin to slave masters. My grandfather never farmed again, but when he ultimately settled in New Jersey he tended a beautiful vegetable garden on a plot next to his home. As a child, I was so amazed when he pulled carrots out of the ground. I believe that the garden represented a piece of the past that he held close to him.

GrowNYC: Cotton is such a beautiful plant with such a violent history here in the United States. What kind of reactions do you get when you tell people about your project?

LaChaun: This is a great question, but it is difficult to answer because each person's experience will differ depending on who they are, where they come from and their personal circumstances and surroundings. For me, the South is full of energy, and that energy varies from place to place. For instance, I live in a very small rural community in an unincorporated city called Pineland, located in Lowcountry South Carolina. It is further inland but the Sea Islands known for the Gullah Geechee culture is no more than an hour away. The most recent census says the area is 90% African American. Everyone that lives around me knows each other and is related in some way. That being said, about 20 minutes from where I live is a confederate flag monument. This represents the racial climate that is often covert. I haven't faced or witnessed any atrocities in my interactions, but I can attest to the lack of development and resources in the overall South--specifically how it affects rural black communities. The expression poverty is expensive is very real in the rural South, whether it be paying a premium for necessities like utilities and internet (which many people don’t have) or traveling for an hour or across state lines for a minimum wage job. The cost of living is low but the absence of opportunity is high. The lack of infrastructure has made it difficult to create generational wealth that can lead to independence and development within these communities.

The land that I live and work on was passed down through the generations from the Rivers brothers who were former slaves. Therefore, everyone living on the land is related and they collectively own it and the houses on the property. This is the reality for most rural southern communities. Although this is ownership there is very little development other than housing. The history of this land is one not to be confused with a plantation. I say this because many people make that assumption. Plantations still exist, however, because they have so much land they are being converted into "private spaces" such as golf courses. This is problematic for several reasons but mainly because they keep the plantation aesthetic. These plantations are located in rural areas so they provide jobs, but these are hospitality jobs which, given the race and class structure of the South, eerily echo the past. I’ve given these examples with hopes to convey the complexities and juxtapositions throughout the rural South that makes trying to pinpoint what land, property and agriculture “means” difficult.

When we talk about farming and working the land, specifically in the South, the stigma left by slavery still exists. However, I get the sense that native southerners' relationship to these stigmas is different than those who’ve moved up north generations ago. Seeing cotton fields isn’t an oddity in the South. Many black Baptist churches are on land that grows cotton. Cotton decor is a staple in many southern homes, although what it represents in a black home differs from the very popular plantation aesthetic. I have certainly experienced aversion from people when talking about cotton but mostly before I moved down South. Many people were warning me about the South and how dangerous it was and that the connotation of growing cotton as a black person was problematic. It was incredibly disappointing and discouraging in the beginning, but I didn't give up and I kept researching. Eventually, I learned about naturally colored cotton. Hundreds of varieties of cotton still exist today and it is believed that years ago there were thousands. Within those varieties are shades of cotton that grow in green, reddish-orange browns and even mauve pinks. Very few people know that cotton grows in colors other than white, let alone the history of the plants' origins. Cotton open pollinates, so naturally colored cotton can come from both cross-pollination over the years as well as manually cross-breeding plants. Crossbreeding is a skill that was brought to the US by the enslaved from West Africa whose efforts can be seen in various heirloom southern crops like rice varieties and sea island cotton. It is believed that slaves used it for cloth as well as medicinal purposes. Naturally colored cotton has a rich history in various Indigenous Latin American countries, however, in the US black slaves and native americans, were only allowed to grow it because plantation owners saw no value in it. The “value” has a lot to do with the fiber quality and genetics (which is why it still isn't commercially viable), however the correlation to the people that cultivated it is one not to be missed. Sally Fox is an Organic Bio-Dynamic naturally colored cotton farmer who has made a huge contribution to organic cotton farming. She bred her own variety of commercially viable naturally colored green and brown cotton called FoxFibre. On an episode of my podcast, she tells the history of naturally colored cotton, as well as her struggles developing and bringing it to market. If you are interested in learning more about naturally colored cotton, I highly suggest you give it a listen.

This past year, on a small plot of land (less than a 1/4 acre) I grew Sea Island Brown Cotton (Gossypium Barbadense, native to South Carolina, crossbred by African slaves), Acadian Brown Cotton (Gossypium Barbadense, from rural French Cajuns in New Orleans, Louisiana), and Green Cotton (Gossypium Hirsutum, from Tututepec Oaxaca Mexico). I also grew Indigofera Suffruticosa that I sourced from a plantation in Charleston. This variety of indigo is the same variety that was a cash crop during slavery. Indigo carries the same painful history in South Carolina as does cotton through the South, However many descendants of the Gullah Geechee people use it as a symbol to honor their ancestors. This is what being a farmer and growing represents to me as well. The pain, trauma, and destruction that happened in this country are at the fault of the system created by the founding fathers and plantation masters alike, not at the fault of my ancestors. My work is not to aestheticize their pain but to honor it and use their strength and resilience as a motivation to build upon.

I understand where the aversion comes from and why it exists, but I don’t think it should act as a catalyst to deter Black Americans from agriculture. In fact, I believe the inverse, keeping black folks out of these systems allows the underbelly of the American financial system which was built on slavery to continue to re-invent itself. There is that saying the only way out is the way through. The South is our people's land, and in this country cotton and indigo are our people's crops. It saddens me to see how indoctrinated the vision of those who created these systems has lingered and continued to place obstacles in the journey towards empowerment through self-sustainability. I‘ve learned plenty on this journey; I’ve grown closer to myself, who I am and where I came from. When you do things consciously, they take longer, which is why I understand how difficult getting this project off the ground has been. But what I also know is that if my ancestors could make it through what they had to endure, then I know it is in my blood to push through as well.

Hear more from LaChaun on her podcast, Weave.

March 2020

March 2020 January 2020

January 2020  November 2019

November 2019 October 2019

October 2019 September 2019

September 2019

WHERE TO COMPOST

WHERE TO COMPOST